Long before European colonization, the Willamette Valley was a mosaic of oak woodlands and savannas, conifer forests in the foothills, and riparian forests along waterways. The region’s original inhabitants, the Atfalati-Kalapuyan people, played a pivotal role in maintaining the health of the Oregon white oak ecosystem and had a deep understanding of the region’s abundance.

Although the Atfalati-Kalapuyans did not practice farming in the way we might think of it today, their environment was abundant with stable plant communities, and camas, wapato, tarweed seeds, hazelnuts, berries, and acorns were prominent food sources harvested during the seasonal rounds that took them to various locations across the valley.

The lush and picturesque valley that European settlers mythologized when they colonized the land was a valley shaped by the Kalapuyan people and their sustainable relationships with the land.

Today, existing Oregon white oak habitats still serve as places of abundance and cultural significance, however urban and agricultural development and the suppression of natural and controlled burning of the land have reduced this once dominant oak habitat to a few surviving pockets across the valley– one of which being the Oregon white oak woodland in the Westlake HOA in Lake Oswego.

The collective wisdom of Native American elders and educators, the records of early colonizers, anthropological accounts, and archaeological research all paint a vivid picture of how native peoples were highly skilled managers of their environments. Their actions included the purposeful manipulation of plants, populations, and habitats to enhance yields, maintain sustainable production, and improve the quality of natural resources. These practices were carried out with a remarkable depth of knowledge, generations of honed horticultural techniques, and thoughtful approaches to harvesting.

Harvesting and Processing Acorns – a Sophisticated First Food System

Autumn held a special significance for the Kalapuyan communities residing in the abundant oak savannas of the Willamette Valley. Acorns, the fruit of oak trees, played a vital role in their diet, providing a valuable source of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. This tradition of harvesting and processing acorns extended to other indigenous communities on the West Coast as well, including the Nisqually, Chehalis, Cowlitz, and Squaxin tribes of Washington.

“You’d let the first bunch drop and usually that first bunch that dropped had insects in them, little grubs and things, so you don’t gather those ones yet but wait till a little later, and then as the second bunch drops; those ones will be a lot better shape.”

—Greg Archuleta, Indigenous artist and educator; member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

In their raw state, acorns are bitter and astringent, requiring careful processing before consumption. Different tribal communities employed different methods to make the acorns edible. One common approach involved charring the acorns to extract the edible flesh. After charring, they would either soak the acorns in water or bury them with clay to leach out the bitter substances. The resulting nutritious paste could then be boiled or mixed with other foods.

Another method involved drying the acorns in the sun after gathering, and then storing them in baskets in nearby springs, and utilizing a certain type blue mud to leach the tannins. Other communities would first grind the acorns using tools like mortar and pestles and then pour water over the flour to make a paste.

Mortar and pestle found at the Five Oaks Museum’s This IS Kalapuyan Land exhibit

“We would bury our mortar and pestle at the foot of the oaks each year and come back to the same tree and be able to dig up our mortar and pestle, process the acorns, and then bury them and come back to them next year, pointing to our relationship with the land and how intimate our relationship was with the trees. We could literally bury something and know we could come back and get it each year, and that was done generation over generation.”

—Steph Littlebird, Indigenous artist, writer, and illustrator; curator of This IS Kalapuyan Land; member of Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

“Kalapuyans likely visited the same Oak groves and Camas patches as their parents and grandparents, for hundreds and thousands of years, and so knew exactly where the food was growing and waiting for them to harvest.”

—David G. Lewis, PhD. OSU Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies & Indigenous Studies; member of Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

Waterlogged archaeological sites, also known as wet sites, offer invaluable insights into the indigenous diets of the Northwest, shedding light on parts that might otherwise be underrepresented or lost to history. One such site, the Sunken Village Archaeological Site on Wapato (Sauvie) Island north of Portland, serves as evidence of a well-preserved Chinookan community that thrived from the mid-thirteenth to the mid-eighteenth centuries. This site stands out as the largest acorn pit leaching site along the entire West Coast of North America, encompassing a vast 125-meter wide beach area.

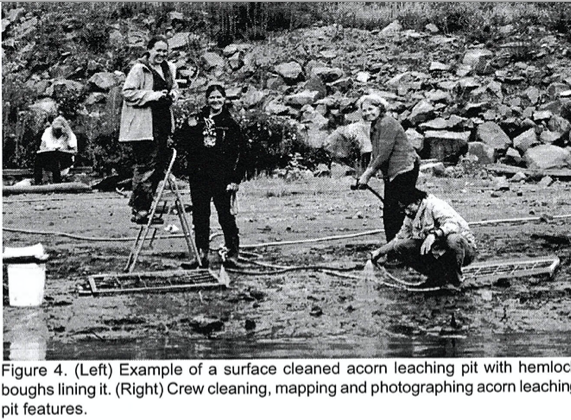

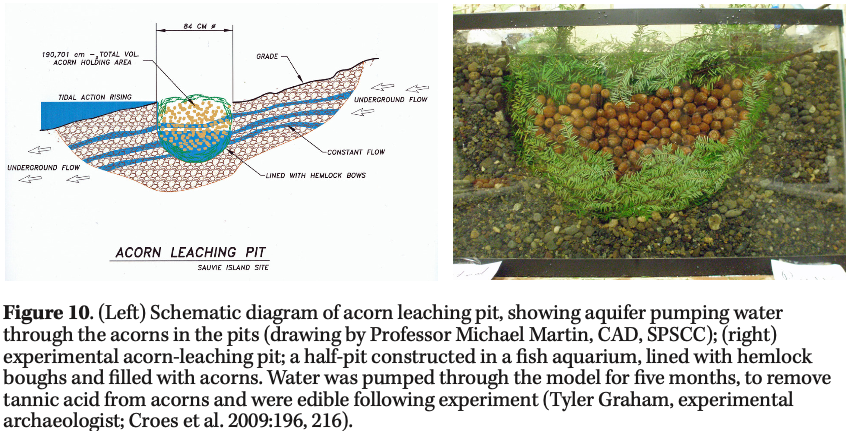

Photo credit: 2008 A Field Report from the Sunken Village Wet Site

At this historic location, archaeologists discovered shallow hemlock-bough-lined pits where acorns were intentionally placed for leaching by the movement of groundwater. At least 100 pits were found where, an estimated 25,000 acorns per pit were thought to be processed, suggesting the potential processing of 2.5 million acorns during bumper crop years (when Oregon white oaks produce a higher yield of acorns followed by two moderate years). Archeologists found Similarities in acorn leaching technology with sites in Japan. Acorn baskets were also recovered with a weaving style that dates back 9,400 years.

The Sunken Village exists now as a National Heritage Landmark site, co-managed by Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Indians.

The technique of passive leaching observed at the Sunken Village Archaeological Site continues to be recognized by tribes today. For instance, the Siletz of western Oregon still refers to acorns leached in stream banks for several months to a year as ‘tusxa’, and acorns are still gathered, stored, and eaten by people living there. Tribal members from Siletz, Grand Ronde, and Warm Springs tell stories of mashing acorns to create a common soup or stew stock.

Summer Homes

In summer, Kalapuyan people lived in temporary windbreak shelters set under large oak trees as they moved from one resource to another in camps. The Atfalati-Kalapuya camped for hundreds of years in an oak meadow called chatakuin, which meant place of the big trees. The site later became a gathering spot for early pioneers. This area is now known as the Five Oaks historic site in Hillsboro Oregon. The two remaining original trees are thought to be more than 500 years old.

Photo credit: Five Oaks Museum

Cultural Burning of Oak Savannas

Over millennia, Indigenous communities of the Willamette valley utilized regular, low-intensity cultural fires as a way to maintain oak savanna habitat and increase food abundance in the valley. These fires acted as evolutionary agents, influencing the survival and thriving of fire-tolerant plant species in the valley, like Oregon white oaks, and selectively “weeding out” trees and bushes that were not fire-resistant, opening up the landscape. Other documented purposes of the controlled burns include deer hunting, gathering tarweed, pest control, improving acorn yield, and preparing land for berry growth.

The lessons from these ancient land management practices are still relevant today, particularly for forest lands in the Cascades and Coast Range. With the increasing impact of climate change and the consequences of past fire suppression practices over the last 140 years, there is a pressing need for different land management strategies.

One striking example of the impact of halting native burning was seen after settlers stopped the tribes’ traditional fire practices. Within a mere ten years, the settlers witnessed a surge in populations of mice, lice, and grasshoppers, which they struggled to control. These insects and rodents, previously kept in check by the tribal ecological stewardship practices, now thrived without the regular burning.

Understanding and learning from these traditional land management practices can offer valuable insights and solutions for the challenges we face today, particularly in the face of ongoing climate change and the imperative to implement sustainable land management practices.

The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde (which represents many descendants of the Kalapuyan people) is working with state agencies to safeguard the remaining oak savannas and protect local species that face endangerment from decades of fire suppression and the spread of invasive species. These collaborative discussions signify an emerging consensus among land managers, acknowledging the importance of controlled burns in mitigating the spread of Douglas fir forests, reducing fuel buildup that can lead to more intense catastrophic wildfires, and enhancing habitat conditions for critical keystone species like Oregon white oaks.

Top photo: Prescribed burn conducted by the Confederated Tribes of Grande Ronde at Champoeg Prairie to curb invasive plants and facilitate future harvest of culturally important plants like camas. Photo credit: Andy Neill, Institute for Applied Ecology.

Left photo: The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde using controlled fire to clear brush and manage the landscape in the Willamette Valley in September 2022. Photo credit: Michael Sherman / OPB

The protection of local habitats and cultivation of First Foods is inseparable from the traditions and knowledge that are deeply rooted in the Atfalati-Kalapuyan tribal identity. By preserving and revitalizing these practices, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde nurture a profound connection with their ancestral lands and underscore the critical interdependence between their cultural heritage and the well-being of the natural world around them.

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to the following individuals for your trust and for sharing your knowledge and stories:

Steph Littlebird

Greg Archuleta

David G. Lewis

David Harrelson

David Craig

Further Learning:

- Five Oaks Museum’s This IS Kalapuyan Land

- OLWC’s Talk with Steph Littlebird: https://youtu.be/JnYfe-kQMvY

- David G. Lewis, PhD. OSU Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Ethnic Studies & Indigenous Studies. Member of the Grand Ronde: https://ndnhistoryresearch.com/

- Kretzler, Ian Edward: An Archaeology of Survivance on the Grand Ronde Reservation: Telling Stories of Enduring Native Presence

- Indigenous Uses, Management, and Restoration of Oaks of the Far Western United States

- Sunken Village, Sauvie Island

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369114116_Archaeological_Wet_Sites_Indicate_Salal_Berries_and_Acorns_were_Staple_Foods_on_the_Central_Northwest_Coast

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349642895_2008_A_Field_Report_from_the_Sunken_Village_Wet_Site_35MU4

- Greg Archuleta, CTGR, Cultural Education Program nsayka iliʔi: Noble Oaks

- Grand Ronde Tribal Lifeways Documentary