Village on the Lake — an OLWC Project Retrospective

By Allie Molen, OLWC Education & Outreach Specialist

Village on the Lake, a neighborhood nestled on Oswego Lake’s Lily Bay, is home to a 2.2 acre riparian-wetland common area, fondly called “the green bowl,” by some residents. This natural area was carved out long ago by the Missoula Floods, evidenced by the hulking basalt escarpments circling the area. This small pocket of urban forest is special for its blend of upland, riparian and wetland habitat. It contains a significant second growth tree canopy and perennial tributary, Lily Pond Creek, stemming from a small spring at the top of the site and resident stormwater runoff.

The Village on the Lake Homeowners Association reached out to the Oswego Lake Watershed Council to assess the health of their unique and cherished natural area in 2019. It quickly became obvious to our site coordinators that the reality of this “green bowl” was a thick basin of English ivy, Himalayan blackberry, garlic mustard, shiny geranium and laurel, smothering the native understory and leaving entire sections of the tract void of the wildlife that rely on a diversity of native vegetation for habitat and foraging opportunities.

With funding from an Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB) small grant, a partial Village on the Lake HOA match and support from the City of Lake Oswego, OLWC was able to begin working to restore the site.

The active phase of the project was completed last year, and on a Friday morning this past July, OLWC board member, Mike Buck, graciously gave me a walking tour of the site to show off the 450 hours of stewardship work that was put into its recovery.

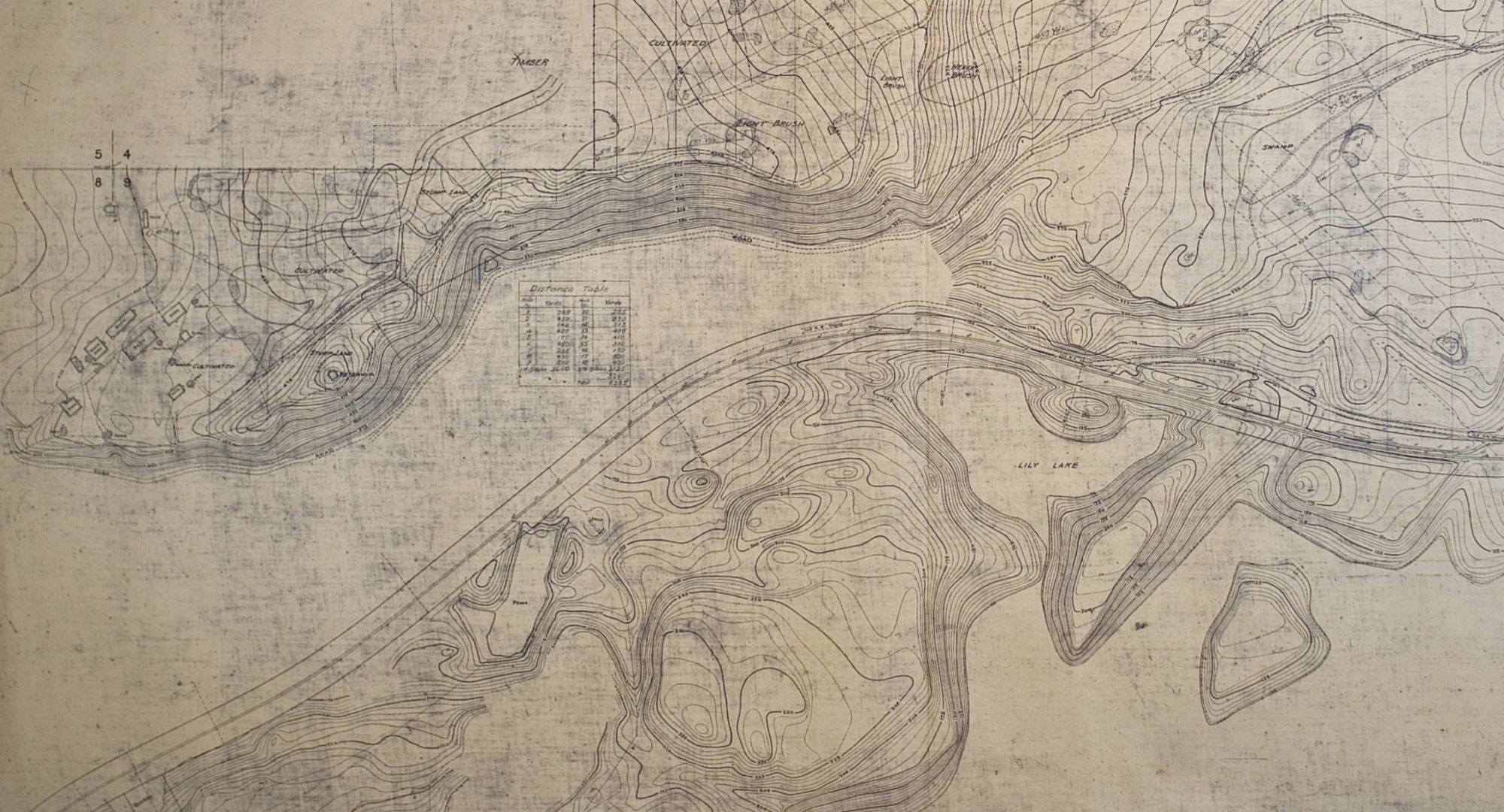

Oregon Iron & Steel Map of Lily Bay, 1923

That morning, as we crossed a residential street and ducked beneath an adjacent property owner’s plum tree that marks the site’s entrance, I experienced an immediate shift in my own energy. The temperature cooled beneath the canopy shade and the area held the scent of tree resin and that bracken, earthy smell distinct to wetland areas. The sound of lawnmowers and traffic on Iron Mt Blvd became muffled by the tree buffer and my head felt clearer and my hearing sharper. Mike was already lengths ahead of me, his mobility unhindered by the uneven terrain. As the main project coordinator for Village on the Lake and given the number of hours he’s worked on this site, I imagined he’d been down this path hundreds of times before.

If you’ve ever met Mike in a natural setting, it’s obvious he is an expert ecologist, but also a deep and critical thinker. He began the tour with a disclaimer: he wants to frame this project narrative with a few questions: who are we, what do we value and how do we want the world to be experienced?

In between the contemplation of those questions Mike would stop to identify rocks with licorice ferns growing in crevices and entire patches of the forest floor that were only recently revealed beneath the thick matts of English ivy. He remarked on the empty dens of animals he found, quoting the pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus: “Nature is wont to hide herself.” Before restoration work began, there was a disquieting weight in the absence of life forms within the site: birdsong, insect humming, kids playing, the lack of native resting grounds for bees, dragonflies and hummingbirds.

We made our way to the wetland area where water pools after periods of prolonged precipitation. Mike began to identify different species of native rushes and sedges that have regenerated since the project’s beginning: slough sedge, spreading rush. There was snowberry and Douglas spirea and thimbleberry. The ground was soft and I was looking for ducks. At one point Mike spotted a slug roughly the size of our native banana slug, but the color of Scots pine bark.

“Sorry slug,” he said and casually and apologetically pierced it into the ground with a sharp stick laying nearby. I think I was only briefly startled; I can respect one’s lack of sympathy for invasive slugs; and besides Mike had already turned around, 20 steps ahead of me again.

Choosing an appropriate plant palette for Village on the Lake was deliberate with careful consideration for what was already prospering in the area. Scrupulous decisions were made on the seeding and planting methods and choices of native species that possess overlapping ecological benefits, high survival potential and coexist well with other species.

Mike led the way between rocks still threaded with decomposing nets of English ivy. We passed stinging nettle, fringecup, oceanspray, ninebark and dogwood, species that regenerated on their own and species that were installed by stewards.

At one point Mike said pensively from in front of me, “You know, many people forget to take the time to look up.” Admittedly, my eyes were mostly peeled to the ground so I didn’t lose my footing (and also looking for coyote scat, because I guess I have an invested interest in coyote scat.). So I followed his lead and looked up into the matrix of sky, clouds, tree canopy and basalt escarpments. On a few of the pinnacles I spied the crimson bark of Pacific madrones and the spiky leaves of Oregon grape clinging to the escarpments.

Mike also described the different manual and mechanical techniques they used to remove the ivy from the landscape. Some areas were easier to treat than others. In the southern section of the HOA property, the ivy was younger, so the roots and stems were easier to remove by hand. But in other areas, removal was long and tedious, and required herbicide application. The steep, rocky terrain, poison oak and large holly and laurel bushes made mobility difficult. Much of the ivy was intertwined with natives like sword fern and trailing blackberry. The topography and shallow soil also made choosing appropriate species tricky. Some areas of the forest floor above 5-6 inches of bedrock, took centuries to build the soil.

We walked past more towering piles of decomposing ivy vines, trunks of firs trellised with dead vines starting 6 feet above the base of the trunk. Mike made an encouraging discovery: a few patches of maidenhair fern peeking out of a tributary, their lacelike fronds creating fragmented shadows on the ground beneath them. More evidence of life forms that were emerging after the blanket of ivy was lifted.

Invasive species removal was conducted by OLWC staff, volunteers, and Wisdom of the Elders LLC. Volunteers contributed over 450 hours of their time removing weeds, coordinating with landowners, planting, maintaining, and monitoring restoration efforts. One adjacent homeowner allowed stewards to use their water to nourish the small saplings that were planted. Over the course of two years, 200 native shrubs and trees 50 fringecup and 1200 plugs of rushes and sedges were planted and a variety of other herbaceous native species were seeded to create greater biodiversity in the area previously dominated by a monoculture sea of English ivy.

Additionally, there was also a hydrological dimension of stormwater mitigation improvement and reduced impacts of erosion. Intake and outtake pipes that had been filled with sediment resulting in compromised functioning were cleared. Native species with longer roots help to stabilize soil, absorb precipitation and filter stormwater.

(Camassia leichtlinii)

Ensatina eschscholtzii

Western Maidenhair Fern

Adiantum aleuticum

I asked Mike what residents of this neighborhood could do to help ensure the health and longevity of this site. He commented that habitat integrity is not just vegetation, it’s soil structure, phenology, local conditions and microclimates. On top of that, healthy landscapes are reliant on a bit of chaos, small disturbances. When we’re taught to categorize, to want to manicure and polish everything into a formal, aesthetically pleasing garden, we lose that chaotic complexity and balance. Humans are responsible for prolonged care of the land, but there should also be a subservience to natural processes that already exist. There needs to be more care for understanding what’s beneficial to the entire ecosystem as well as protection for keystone species that hold the system together.

I thought that the landscape of Village on the Lake did look healthier and more complex, taking on that chaotic quality he referred to. But it’s evident that this endeavor took an incredible amount of human labor to remove the species, keeping other species from regenerating and thriving and ensuring the installed species survived. The drive for long term maintenance is integral to the survival of this landscape. I thought about the watershed council’s role in the community, the opportunities we have to share these labors of love. We have stewards like Mike and other volunteers who worked on Village on the Lake who have a wealth of contagious enthusiasm to spread, even when the initial project is closed and the funding has ended. How do we do that most effectively? I am still contemplating that within my own role as Education and Outreach Specialist.

I had walked through the Village on the Lake tract of land a handful of times before, but that Friday it felt new. Mike had given the area more color and contour. At the end of the walking tour, as we exited the site back into the urban whir of lawn equipment and vehicle noises, Mike quoted Kathleen D. Moore’s passage about small pockets of good work.

“From these sheltered pockets of moral imagining, and from the protected pockets of flourishing, new ways of living will spread across the land, across the salt plains and beetle-killed forests. Here is how life will start anew. Not from the edges over centuries of invasion; rather from small pockets of good work, shaped by an understanding that all life is interdependent, and driven by the one gift humans have that belongs to no other: practical imagination – the ability to imagine that things can be different from what they are now.”

—Kathleen D. Moore